Arnold Bertonneau

Introduction

The 1877 Fillmore School register lists Arnold John Bertonneau as an eight-year old boy born in New Orleans. His father, Arnold E. Bertonneau, was listed as a clerk. The family lived on Love St. (now Rampart St.) near Columbus St. Of interest, the school register does not classify Arnold John as a student who was transferred to “a colored school.” However, Arnold John was most likely forbidden to attend the Fillmore School because his father filed a lawsuit in November 1877 questioning the constitutionality of the city school board’s resegregation policy. Like many Creoles of color families, the Bertonneau family history shows its long quest for racial justice and equality. The family was particularly notable as its efforts went beyond the city boundaries and also affected national politics and the discussion of suffrage and civil rights.

Arnold Bertonneau (1834-1912)

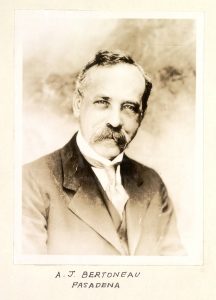

Arnold Bertonneau (photo courtesy of Thomas F. Bertonneau)

Arnold Bertonneau was born on February 4, 1834 to Louis and Marie U. Auguste Bertonneau, both free persons of color. While many of his antebellum activities remain unknown, it is likely that he had entered the circles of Creole leaders by the 1850s. He was a member of La Société d’Economie d’Assistance Mutuelle at least by 1859 and supported La Société Catholique pour L’Institution des Orphelins dans L’Indigence, also known as the Couvent Institute.

The Civil War

From the beginning of the Civil War, Bertonneau expressed his strong desire for full freedom and equality. His efforts, however, took a winding path. At the outbreak of the war, he volunteered for the First Louisiana Native Guard of the Confederate Army. The First Native Guard consisted of free people of color. Bertonneau’s turning point was the occupation of New Orleans in May 1862. Six months later, on October 1, he volunteered as a Union solder. On October 12, he was commissioned as an officer in Company H. U.S. Colored Troops 74th Infantry Regiment. After his resignation of the roll in March, on July 4, 1863, he was mustered in Company E, Louisiana Sixth Infantry Regiment as a captain and served for 60 days.

Universal Suffrage

Following his resignation, Bertonneau shifted his focus from military efforts to universal suffrage. New Orleans offered a particular venue for civil rights as the largest port city in the Gulf South under the Union control. Bertonneau and his fellow community members foresaw that the future challenge would be how to guarantee freedom after the war. Suffrage was his answer. In spite of Bertonneau’s hope, white leaders rejected universal suffrage as being premature. On December 8, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln even affirmed the limitation of suffrage to white men as part of his reconstruction doctrine.

Excerpt from L’Union, April 14, 1864

In response to the president’s decision, in January 1864, Creoles of color took a direct action for black suffrage. First, they petitioned against limited suffrage and collected a thousand signatures from free people of color in New Orleans. Some of the petitioners were or became parents of Fillmore School students: Paul Trévigne, A. L. Chisse, Leopord Guichard to name a few. Arnold Bertonneau was chosen as one of the delegates to bring the petition to the North. With Jean Baptiste Roudanez (a brother of Louis Charles Roudanez, the founder of L’Union and the New Orleans Tribune), Bertonneau met President Lincoln on March 12 and abolitionists in New England later that spring. One of his speeches was published in the Liberator as“Every Man Should Stand Equal Before the Law” in April, 1864. Bertonneau’s and Roudanez’ trip was one of the first direct challenges to dominant opinions toward universal suffrage in the middle of the Civil War. After his return to New Orleans, Bertonneau continued his political action. He committed himself to the new Republican Party in Louisiana and also began advocating for civil rights. In 1867, he participated in the state constitutional convention as one of the first Black delegates and contributed to the ratification of universal suffrage and desegregation of public accommodation.

Marriage

As his efforts succeeded, in April 1868, Bertonneau married Eulalie Marie Adelaide Monfort, a free woman of color of interracial descent. A year later, their first child Arnold John was born. In addition to Arnold John, the couple had three other children, Francois Henry (b. 1871), George Louis (b. 1876), Joseph B. (b. 1878). Toward the end of the 1860s, Bertonneau’s presence in Louisiana politics gradually diminished perhaps because of his family responsibility. He eventually supported his family by holding several positions at the Customs House during the 1870s. Yet, he remained committed his Creole community as a prominent leader. For instance, he was on the board of directors of the Couvent Institute during the same period.

Bertonneau v. the Board of Directors

When the Orleans Parish school board decided to resegregate the city schools in 1877, Bertonneau reappeared in public as one of the parents filing a lawsuit against the school board. In September 1877, a month before the school started, Paul Trévigne asked the Sixth District court of New Orleans for an injuction to halt resegregation, but failed to prevail (Paul Trévigne v. the Board of Directors, 31 La. Ann.0105). Next, Ursin Dellande sued George H. Gordon, the principal of the Fillmore School, but lost at the Sixth District Court on November 13. Not coincidentally, on the same day, Bertonneau petitioned Principal Gordon to admit his child, Arnold John Bertonneau. In response to Gordon’s immediate refusal, Bertonneau filed a lawsuit in the U.S. Circuit Court, arguing that his child’s eviction from the school was unconstitutional in light of both the Louisiana state constitution and the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Nonetheless, like his predecessors, Arnold Bertonneau lost his case in 1879.

Leaving New Orleans

In 1888, Bertonneau’s first wife, Eulalie died. He then married Julia C. Lacoste three years later. Julia and Arnold had three children, Marie Yvonne (b. 1893), Jeanne (b. 1894) and Sidney J. (b. 1898). Soon after the marriage, Arnold started a new clothing business on 392 Dryades Street (present day 1409 Dryades St.) in Central City, away from the Afro-Creole community in downriver New Orleans. Afterwards, the Bertonneau’s name disappeared from Creoles’ communal activism. Perhaps his successful business kept him away. Arnold John soon joined his father’s business. Their store was known as Arnold Bertonneau and Sons. Racial tension in New Orleans was at its height after 1896 when the Creole community lost its Plessy v. Ferguson court case. Two years after the court decision, the Louisiana state legislature adopted the grandfather clause, which deprived Blacks of their voting rights. In 1900, the Robert Charles Riots devastated many African American communities in the city. As a result, in the early twentieth century, many Creole families left New Orleans for the West or North for better opportunities. The Bertonneau family decided to join this exodus. In 1902, Arnold Bertonneau moved to California with his wife and children and crossed the color line. Arnold died in Pasadena in 1912 at the age of 76.

Arnold John Bertonneau (1869-1924)

Portrait of Arnold J. Bertonneau, Wheeler Scrapbook Collection

The Bertonneau family remained socially active in their new city. Using his skills and knowledge in business, Arnold John succeeded in grocery and hotel business, and became an organizer of the American Bank and Trust Company in Pasadena. He was also a member of the Pasadena Board of Trade and Pasadena Merchants’ Association. One of his notable contributions to the Pasadena community is his management of the Rose Parade. He died in 1924 at the age of 55.

Tracing the history of the Bertonneau family, one can see that the Fillmore School was one of many places where they pursued racial equality. The Fillmore School was a microcosm of broader national politics and black migration from the South.

Sources

Primary Sources

- Journal des Seances de la Direction de l’Institution Catholique pour L’Instruction des Orphelines dans l’Indigence, Office of Archives, Archdiocese of New Orleans.

- Bertonneau v. Board of Directors of City Schools et al. [3 Woods, 177]

- Wood, J. W. Pasadena, California, Historical and Personal: A Complete History of the Organization of the Indiana Colony, Pasadena J. W. Wood, 1917.

Newspapers

- L’Union

- Liberator

- New Orleans Tribune

Sources from Ancestry.com

- California Death Index, 1905-1939

- Louisiana Birth Records Index, 1790-1899

- New Orleans, Louisiana, Marriage Recroeds Index, 1831-1920

- U.S. Confederate Soldiers Compiled Service Records, 1861-1865

- U.S. Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865

- U.S. City Directory

- U.S. Census

Photo

- Wheeler, Frank. Wheeler Scrapbook 3, page 336, portrait of Arnold J. Bertonneau. Wheeler Scrapbook Collection. Honnold/Mudd Library Special Collections, The Claremont Colleges Library. Claremont, CA. wsc00003_0336. ccdl.libraries.claremont.edu/cdm/ref/collection/wsc/id/1750, Accessed September 3, 2014.

Selected Secondary Sources

- Devore, Donald E. and Joseph Logsdon, Crescent City Schools: Public Education in New Orleans, 1841-1991. Lafayette: The Center for Louisiana Studies, 1991.

- Hirsch, Arnold R., and Joseph Logsdon eds. Creole New Orleans: Race and Americanization. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1992.

- Ruffin II, Herbert G. “Bertonneau, E. Arnold (1834-1912).” blackpast.org. http://www.blackpast.org/aah/bertonneau-e-arnold-1834-1912.